I’ve still been playing around with Radare2 when I can, and I wanted to see how easy it was to emulate a block of disassembled code using its Evaluable Strings Intermediate Language, or ESIL. For an example, I went back to Eldad Eilam’s Reversing: Secrets of Reverse Engineering.

In Chapter 11, he shows how to reverse a program called Defender.exe that requires a correct username and serial number. There are several protections and anti-reversing tricks this program employs. Specifically, I was looking at some of the sections of code that are encrypted. There are several of these in this program and they all start with a normal looking function followed by some data. That data is decrypted, executed, then encrypted once again.

The executable is available for download in the Downloads section of the book’s page on Wiley. The code I’m going to be referencing is discussed around page 386 (function at 0x4033d1) and page 397 (function at 0x402eef).

Initializing r2 and Observing the Encrypted Code

Assuming you have radare2 and the executable, the initial startup process is straightforward, using the aaa command for initial analysis:

$ r2 Defender.exe -- Here be dragons. [0x00404232]> aaa [x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa) [x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar) [x] Analyze function calls (aac) [ ] [*] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis. [x] Constructing a function name for fcn.* and sym.func.* functions (aan)) [0x00404232]>

Seek to the first function and print it out.

[0x00404232]> s 0x4033d1

[0x004033d1]> pd 100

┌ (fcn) fcn.004033d1 268

│ fcn.004033d1 (int arg_3h);

│ ; CALL XREF from 0x0040423f (entry0)

│ 0x004033d1 55 push ebp

│ 0x004033d2 8bec mov ebp, esp

│ 0x004033d4 81ec2c020000 sub esp, 0x22c

│ 0x004033da 53 push ebx

│ 0x004033db 56 push esi

│ 0x004033dc 57 push edi

│ 0x004033dd 68dd344000 push 0x4034dd

│ 0x004033e2 58 pop eax

│ 0x004033e3 8945e0 mov dword [local_20h], eax

│ 0x004033e6 68fd414000 push 0x4041fd ; "_^[....`@"

│ 0x004033eb 58 pop eax

│ 0x004033ec 8945e8 mov dword [local_18h], eax

│ 0x004033ef b8e5344000 mov eax, 0x4034e5

│ 0x004033f4 8905d6344000 mov dword [0x4034d6], eax ; [0x4034d6:4]=0x4034e5

│ 0x004033fa c745f8010000. mov dword [local_8h], 1

│ 0x00403401 837df800 cmp dword [local_8h], 0

│ ┌─< 0x00403405 7466 je 0x40346d

...snip...

│ │ ; JMP XREF from 0x0040346b (fcn.004033d1)

│ └──> 0x004034d5 68e5344000 push 0x4034e5

│ 0x004034da 5b pop ebx

└ 0x004034db ffe3 jmp ebx

...snip...

[0x004033d1]> pd 10 @0x4034e5

; DATA XREF from 0x004033ef (fcn.004033d1)

; DATA XREF from 0x004034d5 (fcn.004033d1)

┌─< 0x004034e5 7e10 jle 0x4034f7

│ 0x004034e7 b98842c1f8 mov ecx, 0xf8c14288

│ 0x004034ec e68b out 0x8b, al

│ 0x004034ee 2b7f7d sub edi, dword [edi + 0x7d]

│ 0x004034f1 f1 int1

│ 0x004034f2 0289dfc5cbc8 add cl, byte [ecx - 0x37343a21]

0x004034f8 b114 mov cl, 0x14

0x004034fa 214f2a and dword [edi + 0x2a], ecx

0x004034fd 6e outsb dx, byte [esi]

0x004034fe 08fd or ch, bh

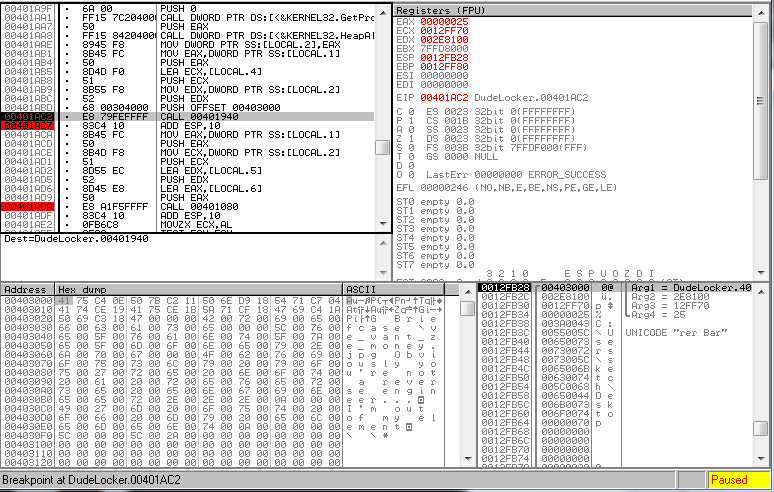

I’m not going to go into detail on everything going on here since it’s covered in the book. The function starts out like all these encrypted functions do, and towards the end there is a PUSH-POP-JMP sequence. The JMP at 0x4034db will move execution to 0x4034e5. When starting disassembly from that line, it’s clear this doesn’t look like legitimate assembly code because it’s encrypted.

Setting up the ESIL Environment

Using ESIL, it’s fairly simple to get radare2 to decrypt this for us. First set up the ESIL environment:

[0x004033d1]> e asm.emu=true [0x004033d1]> e asm.emustr=true [0x004033d1]> e asm.esil=true

The first two commands modify the disassembly so that ESIL information is displayed. The output with asm.emu is verbose, while asm.emustr only shows the most useful information. Setting asm.esil=true shows what the ESIL looks like. The following two snippets show the difference between the asm.emu and asm.esil settings:

[0x004033d1]> s 0x4033d1 [0x004033d1]> e asm.emu=true [0x004033d1]> pd 10 ┌ (fcn) fcn.004033d1 268 │ fcn.004033d1 (int arg_3h); │ ; CALL XREF from 0x0040423f (entry0) │ 0x004033d1 55 push ebp ; esp=0xfffffffffffffffc -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033d2 8bec mov ebp, esp ; ebp=0xfffffffc -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033d4 81ec2c020000 sub esp, 0x22c ; esp=0xfffffdd0 -> 0xffffff00 ; of=0x0 ; sf=0x1 -> 0x3009000 ; zf=0x0 ; pf=0x0 ; cf=0x0 │ 0x004033da 53 push ebx ; esp=0xfffffdcc -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033db 56 push esi ; esp=0xfffffdc8 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033dc 57 push edi ; esp=0xfffffdc4 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033dd 68dd344000 push 0x4034dd ; esp=0xfffffdc0 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033e2 58 pop eax ; eax=0xffffffff -> 0xffffff00 ; esp=0xfffffdc4 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033e3 8945e0 mov dword [local_20h], eax │ 0x004033e6 68fd414000 push 0x4041fd ; esp=0xfffffdc0 -> 0xffffff00

[0x004033d1]> s 0x4033d1 [0x004033d1]> e asm.esil=true [0x004033d1]> pd 10 ┌ (fcn) fcn.004033d1 268 │ fcn.004033d1 (int arg_3h); │ ; CALL XREF from 0x0040423f (entry0) │ 0x004033d1 55 ebp,4,esp,-=,esp,=[4] ; esp=0xfffffffffffffffc -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033d2 8bec esp,ebp,= ; ebp=0xfffffffc -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033d4 81ec2c020000 556,esp,-=,$o,of,=,$s,sf,=,$z,zf,=,$p,pf,=,$b4,cf,= ; esp=0xfffffdd0 -> 0xffffff00 ; of=0x0 ; sf=0x1 -> 0x3009000 ; zf=0x0 ; pf=0x0 ; cf=0x0 │ 0x004033da 53 ebx,4,esp,-=,esp,=[4] ; esp=0xfffffdcc -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033db 56 esi,4,esp,-=,esp,=[4] ; esp=0xfffffdc8 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033dc 57 edi,4,esp,-=,esp,=[4] ; esp=0xfffffdc4 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033dd 68dd344000 4207837,4,esp,-=,esp,=[4] ; esp=0xfffffdc0 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033e2 58 esp,[4],eax,=,4,esp,+= ; eax=0xffffffff -> 0xffffff00 ; esp=0xfffffdc4 -> 0xffffff00 │ 0x004033e3 8945e0 eax,0x20,ebp,-,=[4] │ 0x004033e6 68fd414000 4211197,4,esp,-=,esp,=[4] ; esp=0xfffffdc0 -> 0xffffff00

These options aren’t really needed for the code emulation part, at least as far as I’ve found, but provide some more insight into what r2 will be doing during the emulation. The documentation seems to say that at least asm.emu is needed, but it worked fine for me when I didn’t include that. Maybe more complex code might require it.

[0x004033d1]> e asm.bits=32 [0x004033d1]> e asm.arch=x86 [0x004033d1]> e asm.emuwrite=true [0x004033d1]> e io.cache=true

The first two commands above also don’t seem to be necessary (maybe because they are the defaults and match the file we’re looking at), but probably don’t hurt to ensure r2 will handle the code correctly. The last two are important. They allow r2 to modify memory and enable cache for io changes, respectively.

[0x004033d1]> s 0x4033d1 [0x004033d1]> aei [0x004033d1]> aeim [0x004033d1]> aeip [0x004033d1]> aer oeax = 0x00000000 eax = 0x00000000 ebx = 0x00000000 ecx = 0x004041f9 edx = 0x00000000 esi = 0x00000000 edi = 0x00000000 esp = 0x00177dc4 ebp = 0x00177ffc eip = 0x004033d1 eflags = 0x00000081

These commands finally set up the ESIL environment and display the current register values. First, aei initializes the ESIL VM state, aeim initializes the ESIL VM stack, and aeip initializes the ESIL program counter to the current address. Finally, aer displays the current registry values. The environment is ready to begin emulating the code. You could step through using various debugger-like commands such as aes, aeso, aec, which are all documented on the ESIL page above. The easiest way for this code, though, is to let it execute until just before jumping to the decrypted code.

[0x004033d1]> aecu 0x4034db

[0x004034d5]> pd 3

│ ; JMP XREF from 0x0040346b (fcn.004033d1)

│ 0x004034d5 68e5344000 push 0x4034e5

│ 0x004034da 5b pop ebx

└ 0x004034db ffe3 jmp ebx

[0x004034d5]> pd 10 @0x4034e5

; DATA XREF from 0x004033ef (fcn.004033d1)

; DATA XREF from 0x004034d5 (fcn.004033d1)

0x004034e5 8b4508 mov eax, dword [ebp + 8] ; [0x8:4]=4

0x004034e8 8945b0 mov dword [ebp - 0x50], eax

0x004034eb 8b45b0 mov eax, dword [ebp - 0x50]

0x004034ee 8b4db0 mov ecx, dword [ebp - 0x50]

0x004034f1 03483c add ecx, dword [eax + 0x3c] ; "PE"

0x004034f4 894da8 mov dword [ebp - 0x58], ecx

0x004034f7 8b45a8 mov eax, dword [ebp - 0x58] ; "PE"

0x004034fa 8b4db0 mov ecx, dword [ebp - 0x50]

0x004034fd 034878 add ecx, dword [eax + 0x78]

0x00403500 894db8 mov dword [ebp - 0x48], ecx

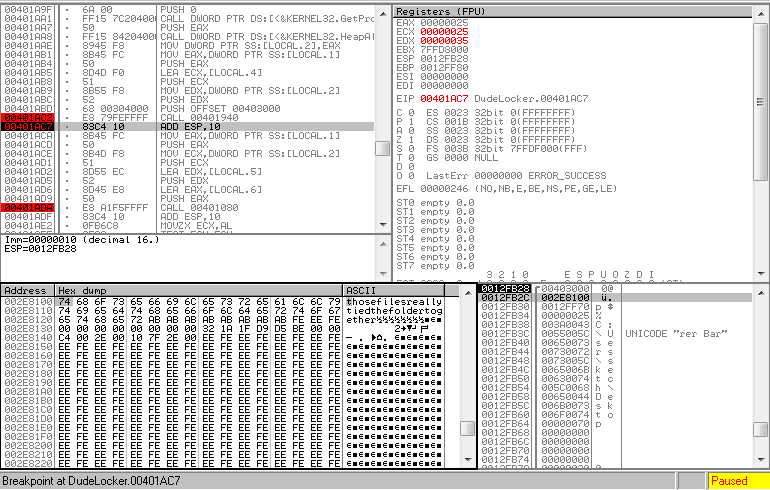

0x4034db contains the “jmp ebx” instruction we looked at earlier and this aecu command tells r2 to emulate code until it reaches instruction 0x4034db. For some reason, r2 stopped at 0x4034d5, but we can see we are at the PUSH-POP-JMP sequence, and if we print the disassembly at 0x4034e5, it’s now decrypted.

Resetting ESIL and Decrypting Another Function

The second code segment starts at 0x402eef.

[0x004034d5]> pd 100 @0x402eef

0x00402eef 55 push ebp

0x00402ef0 8bec mov ebp, esp

0x00402ef2 83ec60 sub esp, 0x60 ; '`'

0x00402ef5 53 push ebx

0x00402ef6 68f62f4000 push 0x402ff6

0x00402efb 58 pop eax

0x00402efc 8945e4 mov dword [ebp - 0x1c], eax

0x00402eff 68e2304000 push 0x4030e2

0x00402f04 58 pop eax

0x00402f05 8945f0 mov dword [ebp - 0x10], eax

0x00402f08 b8fe2f4000 mov eax, 0x402ffe

0x00402f0d 8905ef2f4000 mov dword [0x402fef], eax ; [0x402fef:4]=0x402ffe

0x00402f13 c745f4010000. mov dword [ebp - 0xc], 1

0x00402f1a 837df400 cmp dword [ebp - 0xc], 0

┌─< 0x00402f1e 7466 je 0x402f86 ; unlikely

...snip...

└──> 0x00402fee 68fe2f4000 push 0x402ffe

0x00402ff3 5b pop ebx

0x00402ff4 ffe3 jmp ebx

...snip...

[0x004034d5]> pd 10 @0x402ffe

0x00402ffe b3f8 mov bl, 0xf8

0x00403000 b265 mov dl, 0x65 ; 'e' ; "run in DOS mode....$"

┌─< 0x00403002 7c21 jl 0x403025 ; likely

│ 0x00403004 ce into

│ 0x00403005 c8373783 enter 0x3737, -0x7d

│ 0x00403009 ec in al, dx

│ 0x0040300a 39d6 cmp esi, edx

┌──< 0x0040300c 7614 jbe 0x403022 ; likely

││ 0x0040300e 8e6e0a mov gs, word [esi + 0xa] ; [0xa:2]=0

││ 0x00403011 d98577ff317e fld dword [ebp + 0x7e31ff77]

We can see the same structure in this code: same sequence setting up the function, the PUSH-POP-JMP, and that JMP going to nonsense assembly code.

First, we’ll clear out the ESIL environment to start fresh.

[0x004034d5]> ar0 [0x004034d5]> aeim- [0x00000000]> aei-

These commands clear the registers, de-initialize the VM stack, an de-initialize the VM state. Now we’ll run all the commands at once, this time stopping at the JMP at 0x402ff4.

[0x00000000]> s 0x402eef

[0x00402eef]> aei

[0x00402eef]> aeim

[0x00402eef]> aeip

[0x00402eef]> aer

oeax = 0x00000000

eax = 0x00000000

ebx = 0x00000000

ecx = 0x00000000

edx = 0x00000000

esi = 0x00000000

edi = 0x00000000

esp = 0x00178000

ebp = 0x00178000

eip = 0x00402eef

eflags = 0x00000000

[0x00402eef]> aecu 0x402ff4

[0x00402fee]> pd 10 @0x402ffe

0x00402ffe 33c0 xor eax, eax

0x00403000 40 inc eax

┌─< 0x00403001 0f84c0000000 je 0x4030c7 ; unlikely

│ 0x00403007 0f31 rdtsc

│ 0x00403009 8945f8 mov dword [ebp - 8], eax

│ 0x0040300c 8955fc mov dword [ebp - 4], edx

│ 0x0040300f a100604000 mov eax, dword [section_end..data] ; [0x406000:4]=-1 ; LEA section_end..data ; section_end..data

│ 0x00403014 8945b0 mov dword [ebp - 0x50], eax

│ 0x00403017 8b45b0 mov eax, dword [ebp - 0x50]

│ 0x0040301a 833800 cmp dword [eax], 0

As you can see, the emulation worked and the code is now decrypted.

Scripting the Commands with r2pipe

All of these commands can be put in a simple Python r2pipe script as follows:

$ cat defender.py

import sys

import r2pipe

r = r2pipe.open()

r.cmd('aaa')

r.cmd('e asm.emu=true')

r.cmd('e asm.emustr=true')

r.cmd('e asm.bits=32')

r.cmd('e asm.arch=x86')

r.cmd('e asm.emuwrite=true')

r.cmd('e io.cache=true')

r.cmd('s 0x4033d1')

r.cmd('aei')

r.cmd('aeim')

r.cmd('aeip')

r.cmd('aer')

r.cmd('aecu 0x0040346b')

r.cmd('ar0')

r.cmd('aeim-')

r.cmd('aei-')

r.cmd('s 0x402eef')

r.cmd('aei')

r.cmd('aeim')

r.cmd('aeip')

r.cmd('aer')

r.cmd('aecu 0x402ff4')

Finally, the script can be executed, then the functions reviewed as follows:

$ r2 -i defender.py Defender.exe

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[ ] [*] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis.

[x] Constructing a function name for fcn.* and sym.func.* functions (aan))

-- r2 -- leading options since 2006

[0x00402fee]> pd 10 @0x4034e5

; DATA XREF from 0x004033ef (fcn.004033d1)

; DATA XREF from 0x004034d5 (fcn.004033d1)

0x004034e5 8b4508 mov eax, dword [ebp + 8] ; [0x8:4]=4

0x004034e8 8945b0 mov dword [ebp - 0x50], eax

0x004034eb 8b45b0 mov eax, dword [ebp - 0x50]

0x004034ee 8b4db0 mov ecx, dword [ebp - 0x50]

0x004034f1 03483c add ecx, dword [eax + 0x3c] ; "PE"

0x004034f4 894da8 mov dword [ebp - 0x58], ecx

0x004034f7 8b45a8 mov eax, dword [ebp - 0x58] ; "PE"

0x004034fa 8b4db0 mov ecx, dword [ebp - 0x50]

0x004034fd 034878 add ecx, dword [eax + 0x78]

0x00403500 894db8 mov dword [ebp - 0x48], ecx

[0x00402fee]> pd 10 @0x402ffe

0x00402ffe 33c0 xor eax, eax

0x00403000 40 inc eax

┌─< 0x00403001 0f84c0000000 je 0x4030c7 ; unlikely

│ 0x00403007 0f31 rdtsc

│ 0x00403009 8945f8 mov dword [ebp - 8], eax

│ 0x0040300c 8955fc mov dword [ebp - 4], edx

│ 0x0040300f a100604000 mov eax, dword [section_end..data] ; [0x406000:4]=-1 ; LEA section_end..data ; section_end..data

│ 0x00403014 8945b0 mov dword [ebp - 0x50], eax

│ 0x00403017 8b45b0 mov eax, dword [ebp - 0x50]

│ 0x0040301a 833800 cmp dword [eax], 0